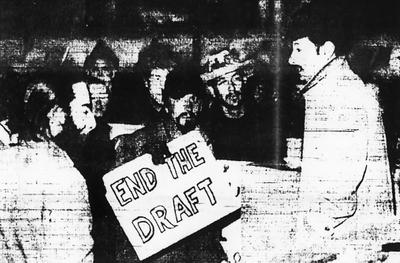

"Much Ado about nothing was what happened when these

sympathizers showed up at the Federal Bldg. to lend moral support

to the refusal of Ed Bortz, right, 20, of the North Side, to be drafted..."

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(published in The New People, Pittsburgh, PA, October 2005)

Jobs Not Guns

by e b bortz

Though I didn’t realize it then, it was a completely natural act for me to openly resist military induction in 1969. I was twenty years old and the Vietnam War was raging. When several of us publicly mailed our personal draft cards back to the Selective Service System, we knew it would only be a matter of weeks before they tried to draft us. I was 1-A and had passed the pre-induction physical with flying colors. My “GREETINGS” letter, “you are ordered to report for induction into the United States Army,” came from the Pittsburgh draft board about four weeks after sending my draft card back.

Things had been brewing inside of me for a long time. I heard Dennis Mora, one of the Fort Hood 3 soldiers that refused to ship out to Vietnam in 1966, saying that he wouldn’t fight in an immoral, illegal war of extermination. I considered myself a “selective conscientious objector,” a point of view not recognized by most local draft boards. Open resistance became the only moral position that made sense to me. I would openly resist and take the consequences.

A few days before I was scheduled to report for Army induction, Dr. Benjamin Spock happened to be in Pittsburgh. We all sat on the floor in a supporter’s home in Point Breeze as Ben told us about some of the

young men he had counseled. Many of them were now refusing, because of conscience, to participate in the military death machine. He had spent his life as a pediatrician and this was part of his work. We all looked around the room at each other, knowing that this might be the last time some of us would be gathering. Several in our group were in various stages of legal wrangles, others not present, were already in jail for the stand they took. But our bond was very much alive with all who had walked before us. Our meeting ended with a short announcement about turning out for my solidarity picket line at 6:30 a.m. at the federal building in the coming week.

I needed to write a statement for induction day. The words had gone through my mind hundreds of times already, but I never had actually written it down. I wasn’t a very well organized selective conscientious objector. Supporters would be showing up, and like previous resisters, I needed to say a few words before going into the federal building to confront the Army.

“Today, I’m refusing induction into the United States Army. My fight is not in Vietnam...my fight is right here in Pittsburgh. Youth in Pittsburgh need jobs and education, not guns. My conscience will not let me participate in this immoral war nor be an accomplice to a military machine that napalms villagers, burns rice paddies, and jails anti-war soldiers who also have refused to kill. I’m prepared to face these authorities, but I refuse to

I needed to write a statement for induction day. The words had gone through my mind hundreds of times already, but I never had actually written it down. I wasn’t a very well organized selective conscientious objector. Supporters would be showing up, and like previous resisters, I needed to say a few words before going into the federal building to confront the Army.

“Today, I’m refusing induction into the United States Army. My fight is not in Vietnam...my fight is right here in Pittsburgh. Youth in Pittsburgh need jobs and education, not guns. My conscience will not let me participate in this immoral war nor be an accomplice to a military machine that napalms villagers, burns rice paddies, and jails anti-war soldiers who also have refused to kill. I’m prepared to face these authorities, but I refuse to

recognize their illegal authority to wage war.”

Induction Day. I rolled up a bunch of copies of my statement for my back pocket, stuck a few anti-war buttons in my front pocket, and started walking down Buena Vista Street from the North Side. It was cold but I was warm with energy, my thoughts crystallized and bumping across the cobblestones, smooth and slippery.

Friends and supporters were getting ready to start the picket line when I arrived at the federal building. I felt self-conscious as chanting started...”Ed Won’t Go...Ed Won’t Go.” Other inductees were already going into the federal building as I finished up my little speech, gave my dad a hug, and headed up the steps and on through the thick glass doors.

Soldiers in the lobby herded us inductees to the assembly room upstairs where a sergeant began giving his standard pep talk about how great it was to be in the Army fighting “for freedom.” As the other inductees were squirming anxiously in the school room-type chairs, I decided it was time for me to make my move.

I pulled out my statements and buttons and started passing them out to a bunch of surprised, scared young guys. In a raised clear voice, I was able to get out a few phrases like “There’s no way I’m going to cross the line...this war is immoral and illegal.” Within a minute, a couple of soldiers were escorting me out of the assembly

room and placing me in a small well-lit “classroom” with a round wooden table and a tape recorder plunked down in the middle.

“So, Bortz, what do you want to say?” a clean-cut, flat-top lieutenant asked.

“I already made my statement, I’m sure you have it on tape.”

“But what do you want to say now?”

“I’ve made my statement.”

A few minutes of this and the officer finally gave up and walked out. I sat and examined every aspect of that room for at least an hour, alone with my own thoughts. Now what? Was I going to jail?

The lieutenant finally returned and took me into a large office space with many desks. I was told to sit down next to an empty desk and then left alone. In fact, of the twenty or so desks in this room, all were empty. After a

few minutes a soldier (clerk?) came in and sat at his desk twenty feet away from me. He said nothing and made no eye contact. He seemed to be continuously fiddling with paper and pencil. I thought it was kind of humorous. Maybe he was an auditor looking for those lost millions.

But then something strange happened. The clerk started whistling, in perfect tone, the socialist anthem, “The Internationale.” Guess he was waiting for me to join in, but he never invited me, and I never said a word. I certainly didn’t want to ruin the ambiance of his moment. Maybe the officers needed something on tape, since I wasn’t inclined to give them anything. But it was a funny, spooky diversion nonetheless.

The clerk finally left and I sat alone again, feeling that the longer this whole thing dragged on, the more likely it might end in a stalemate. If I was going to be arrested, why haven’t they done it yet? Or maybe I was already under arrest but didn’t know it? I couldn’t get over how incredibly neat and orderly every desk was. Did they

do any real work here?

It seemed like two hours before the lieutenant finally returned. “We’re going to let you go today while we review your case. Don’t leave town.”

Why shouldn’t I leave town, I thought, but didn’t ask. Was this an order?

“You’ll be getting something in the mail with our determination. You can leave now.”

I didn’t need to hear anymore. I stood up, looked the lieutenant in the eye, and said “Peace!” as I walked out and didn’t look back.

Everyone had left the federal building by then, except for my pregnant sister-in-law Gerry. We went for coffee nearby so I could tell her the whole story.

The “determination” letter finally came a few weeks later saying that the Army had decided not to pursue my case any further. They didn’t want me, but said that I could appeal their decision. Maybe the courts were plugged up, maybe my refusal to sign the “non-subversive” form was enough, maybe there were other legalities, or maybe there were already too many hell-raisers for them to handle.

Conscientious objection and draft resistance cases filled the courts for years to come. Thousands went to Canada. Anti-war soldiers tossed their medals back at the Capitol, others took their own lives. Three million Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Americans never made it through alive.

In the end, we all make choices.

“universal soldier...his orders come from far away no more

they come from him and you and me and brothers can’t you see this is not the way we put an end to war.”

--- buffy sainte-marie

**********************************************************

Induction Day. I rolled up a bunch of copies of my statement for my back pocket, stuck a few anti-war buttons in my front pocket, and started walking down Buena Vista Street from the North Side. It was cold but I was warm with energy, my thoughts crystallized and bumping across the cobblestones, smooth and slippery.

Friends and supporters were getting ready to start the picket line when I arrived at the federal building. I felt self-conscious as chanting started...”Ed Won’t Go...Ed Won’t Go.” Other inductees were already going into the federal building as I finished up my little speech, gave my dad a hug, and headed up the steps and on through the thick glass doors.

Soldiers in the lobby herded us inductees to the assembly room upstairs where a sergeant began giving his standard pep talk about how great it was to be in the Army fighting “for freedom.” As the other inductees were squirming anxiously in the school room-type chairs, I decided it was time for me to make my move.

I pulled out my statements and buttons and started passing them out to a bunch of surprised, scared young guys. In a raised clear voice, I was able to get out a few phrases like “There’s no way I’m going to cross the line...this war is immoral and illegal.” Within a minute, a couple of soldiers were escorting me out of the assembly

room and placing me in a small well-lit “classroom” with a round wooden table and a tape recorder plunked down in the middle.

“So, Bortz, what do you want to say?” a clean-cut, flat-top lieutenant asked.

“I already made my statement, I’m sure you have it on tape.”

“But what do you want to say now?”

“I’ve made my statement.”

A few minutes of this and the officer finally gave up and walked out. I sat and examined every aspect of that room for at least an hour, alone with my own thoughts. Now what? Was I going to jail?

The lieutenant finally returned and took me into a large office space with many desks. I was told to sit down next to an empty desk and then left alone. In fact, of the twenty or so desks in this room, all were empty. After a

few minutes a soldier (clerk?) came in and sat at his desk twenty feet away from me. He said nothing and made no eye contact. He seemed to be continuously fiddling with paper and pencil. I thought it was kind of humorous. Maybe he was an auditor looking for those lost millions.

But then something strange happened. The clerk started whistling, in perfect tone, the socialist anthem, “The Internationale.” Guess he was waiting for me to join in, but he never invited me, and I never said a word. I certainly didn’t want to ruin the ambiance of his moment. Maybe the officers needed something on tape, since I wasn’t inclined to give them anything. But it was a funny, spooky diversion nonetheless.

The clerk finally left and I sat alone again, feeling that the longer this whole thing dragged on, the more likely it might end in a stalemate. If I was going to be arrested, why haven’t they done it yet? Or maybe I was already under arrest but didn’t know it? I couldn’t get over how incredibly neat and orderly every desk was. Did they

do any real work here?

It seemed like two hours before the lieutenant finally returned. “We’re going to let you go today while we review your case. Don’t leave town.”

Why shouldn’t I leave town, I thought, but didn’t ask. Was this an order?

“You’ll be getting something in the mail with our determination. You can leave now.”

I didn’t need to hear anymore. I stood up, looked the lieutenant in the eye, and said “Peace!” as I walked out and didn’t look back.

Everyone had left the federal building by then, except for my pregnant sister-in-law Gerry. We went for coffee nearby so I could tell her the whole story.

The “determination” letter finally came a few weeks later saying that the Army had decided not to pursue my case any further. They didn’t want me, but said that I could appeal their decision. Maybe the courts were plugged up, maybe my refusal to sign the “non-subversive” form was enough, maybe there were other legalities, or maybe there were already too many hell-raisers for them to handle.

Conscientious objection and draft resistance cases filled the courts for years to come. Thousands went to Canada. Anti-war soldiers tossed their medals back at the Capitol, others took their own lives. Three million Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Americans never made it through alive.

In the end, we all make choices.

“universal soldier...his orders come from far away no more

they come from him and you and me and brothers can’t you see this is not the way we put an end to war.”

--- buffy sainte-marie

**********************************************************

2 comments:

Quite a story.

thank you.

Post a Comment